Underwriting People

Integrity vs. Flexibility

"It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change." — Charles Darwin

In the high-stakes theatre of private equity and venture capital, we spend an inordinate amount of due diligence time reviewing hard skills. We obsess over a GP’s attribution, their proprietary deal flow, and the clinical precision of their underwriting. But as any seasoned LP will tell you, funds don’t usually fail because the math was wrong; they fail because the people were.

When you strip away the Bloomberg terminals and the vanity metrics, you are left with character. Specifically, the tension between two seemingly opposing forces: integrity and flexibility.

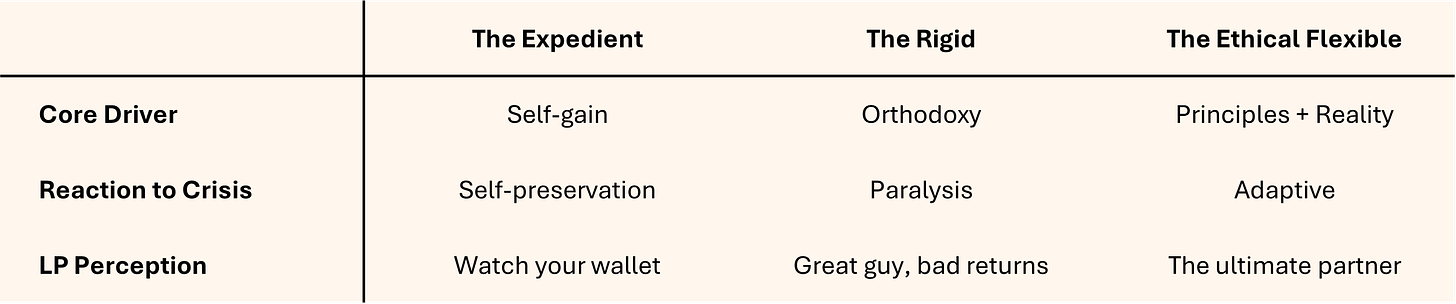

In my time observing the rise and fall of managers, I’ve realised that most LPs treat these as a binary choice. You are either a person of your word (the stoic) or a person of the moment (the pivot master). This is a false dichotomy that leads to two specific failure modes: the Expedient and the Rigid.

To survive a decade-long fund cycle, a GP must realise that integrity without flexibility is brittle, but flexibility without integrity is hollow. As an allocator, your job is to identify which side of the line your manager walks when the macro environment shifts away from easy mode.

High Flexibility, Low Integrity

At the bottom of the hierarchy, we find the Expedient, managers characterised by moral flexibility. The Expedient GP is a master of the pivot: not the celebrated and encouraged start-up pivot, but the ethical pivot of an opportunist. They adapt to maximise self-gain, often compromising their stated strategy to chase whatever is currently fetching the highest marks.

They are the first to style drift without telling LPs. They might withhold bad news from the quarterly call, and aggressively mark up a bridge round to inflate the IRR for a Fund II fundraise.

This creates a low-trust environment. When a GP enforces rules only when it suits them, i.e. holding founders to strict KPIs while ignoring their own concentration limits, they lose the mandate to lead.

Watch for leadership duplicity. If the GP’s internal team has high turnover or if they treat service providers poorly, they are likely treating your capital with the same disregard for long-term partnership.

High Integrity, Low Flexibility

On the opposite end, we have the Rigidly Ethical. These are the managers you would trust with your life, but perhaps not with your portfolio in an ever changing macro. They possess iron-clad moral principles but have a high resistance to changing their methods or adapting to new market realities.

They prefer black-and-white scenarios. If they told you in 2021 they were a growth-at-all-costs fund, they will continue to burn cash into a high-interest-rate wall because to do otherwise feels like breaking their word.

While they are inherently trustworthy, they struggle with innovation. They reject new ideas or asset class developments because it does not fit their existing, decade-old worldview.

These managers suffer from high burnout. When forced to adapt to complex, fast-moving situations, they become paralysed, and would rather go down with the ship than change their ways.

The Goal

The holy grail of manager selection is Ethical Flexibility. This is the ability to be highly responsive to a changing environment, modifying methods, sectors, and tactics, without ever compromising the fundamental principles of fiduciary duty and transparency.

Flexibility should not be confused with a lack of rules. Rather, it is about being responsive without losing your North Star. The best GPs are those who can sit across from their LPs and say: “The market has changed, and our old framework is redundant. Here is how we are adapting our tactics to protect your capital, while maintaining the same commitment to excellence we promised on day one.”

An Allocator’s Lens

In the private markets, alpha is a function of time, but survival is a function of character. Whether the strategy is to hunt for unicorns or EBITDA, your greatest enemy is a manager who panics. The Rigid GP panics by doing nothing; the Expedient GP panics by doing anything to save themselves.

We often talk about the ‘J-curve valley of death’ as a financial hurdle, but it is primarily a psychological one. You cannot navigate the boring middle years with a manager who treats their principles as a commodity or their methods as a religion.

In a decadal game, you back a person (the alpha generator) within a thesis you believe in (the beta). When underwriting their strategy, you are also underwriting their ability to respond to the inevitable regime shift. You need the rare manager who is structurally incapable of folding when the terrain stops matching the map.

Some people watch gladiator clips to get pumped up, I read James’s Substack. Nice one James!